Saturday, August 01, 2015

Through the Storm...

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=izrk-erhDdk[/embed]

Thursday, July 23, 2015

"Reading" the Newspaper

It’s at a minimum interesting -- and usually instructive -- to “read” a newspaper, i.e. to be attentive to the kinds of stories that the editors present, and what that tells us both about them and about us.

When it comes to the cultural analysis that I call being a movie “critic”, one of the forms that I find particularly fascinating is to “read” the newspaper.

The quotation marks there are important, of course… I’m not talking about just reading the stories found in a newspaper, but about stepping back and being attentive to the nature and number of stories the paper contains.

In this post I’ll explain what I mean by this, give some examples about how to “read” a newspaper, and then explain why it’s important to “read” a newspaper.

To state the obvious, newspaper-publishing -- like most journalism in general -- requires some form of sales. That’s in no way to disparage journalists; I believe that most of them, especially print journalists, believe in the important role that a free press plays in a democratic society. But it goes without saying that a newspaper’s writers and editors will find themselves unemployed if their paper sells too few copies.

This means that an editor has to balance the content of a paper between the sorts of stories that he thinks people need to know about with the sorts of stories that he thinks they’ll want to know about. So one interesting way of reading a paper is to take each story and attempt to discern if it’s a story published for the public interest (what they need to know about) or one published for the public’s interest (what they want to know about), or -- as sometimes happens, of course -- both. And we can then take the next step of discerning why an editor might think a story is important and/or interesting.

Here’s an example: I recently visited my in-laws and was reading their local paper, itself a subsidiary of Gannett, which publishes USAToday and owns local papers all over the country. One day’s issue had three front page stories: one -- which dominated the vast majority of the page -- about a state politician’s entrance into the presidential race, another about the sentencing of a 21 year old whose reckless driving resulted in death and major injuries, and a third announcing a fall performance by 80's singer Bret Michaels at a local bar & grill.

Now, why did the paper’s editors decide these three stories were worthy of making the front page instead of any of the other dozen-plus news items in the rest of the paper? Front page space in a newspaper is hugely important, of course, so the editors need to be very deliberate in deciding what makes the front page and what doesn’t. Again, one interesting form of analysis is to consider why the editors have included any story in the day’s paper, but particularly why they’ve chosen to highlight a story by placing it on the front page.

Another way to “read” a newspaper is to be attentive to whether a given story is local, state or national in nature, and an easy way to determine this -- besides paying attention to the topic, of course -- is to pay attention to the byline: is the writer a staffer for the local paper, for the state office (in my in-laws’ example, Gannett’s state bureau), or for the national office (USAToday in this case, or the Associated Press). This is probably the first way I read a paper, for the simple reason that I can get national and even state stories from multiple sources, but when it comes to local news my options are much more limited, and hence I’m usually attentive first to the locally-written stories.

There are other approaches to “reading” a newspaper in this way but these are two that come to mind (and two that can be combined, of course). I’d like now to turn to the question of why “reading” a paper might be important, particularly for Christians seeking to engage the culture.

As I mentioned in the lead paragraph, “reading” a newspaper at a minimum reveals what the editors think is important themselves and what they think the public at large finds important. And because many editors at the national level are successful at the latter -- based on the fact that they are able to sell sufficient numbers of their papers to maintain a national newspaper -- “reading” a newspaper likewise tells us something about what we as a society find to be important as well.

Let’s look back at the example of my in-laws’ local paper and its stories on a state politician’s entrance into the presidential race, on the judicial outcome of a tragic automobile accident and a coming performance by rocker Bret Michaels. All three stories, I’d argue, were included by the editors because they thought their real and prospective readers would find them interesting: watching politics is a national pastime for many Americans, particularly when a state official is involved; we have a (generally) unfortunate obsession with deadly accidents (cf. rubber-necking at an accident come upon); and we have a likewise generally-unfortunate obsession with celebrities, even those whose prime is long past (yes, I’m anticipating possible pushback from the 80’s-hair bands crowd ;-).

So what is it about each of these types of stories that we find compelling? Why are we interested in accidents and celebrities? Our abiding interest in politics is easier to make sense of -- we are talking about our civic leaders, after all. But as has been well-commented on, our presidential campaigns have been becoming increasingly lengthy, and that seems to be happening with our cooperation, if not endorsement and prompting.

What do you think? Why do Americans in general find these sorts of stories so interesting that editors put them on the front cover? And more generally, what have been your findings in “reading” the newspaper?

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

New Comments Spam Blocker

It shouldn't be a problem, but if you can't comment for some reason, let me know by emailing me at chris@chrisburgwald.com.

Sunday, July 12, 2015

Why Not?

If we can’t explain our moral code, we’re building houses on sand for ourselves, our families and our local and national communities.

In this and some upcoming posts I’d like to take step back from Obergefell and its immediate fallout and look at some of the deeper issues which it raises about our society and culture. In this post I’d like to look at the rationale behind our morals, or more precisely, at the need to be able to articulate the rationale behind our morals.

Several weeks back I noted that one of my favorite questions is “Why?” As I stated in that post, it’s essential for us to inquire about why we believe what we believe as Christians.

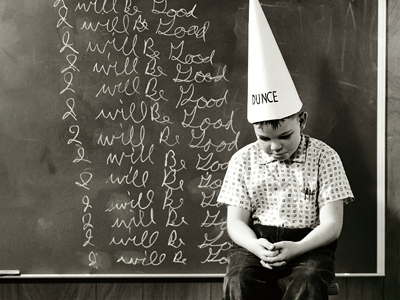

Relatedly, and specifically with regard to morality, it’s likewise essential to ask why we think certain actions are right or good and other actions are wrong or evil. In other words, to put it as I do in the title of this post, it’s essential to ask “Why not”, i.e. “why shouldn’t I/we do action x, y or z?” And yet, it’s my experience that many Americans are unable to give an answer to that question, to explain why x is wrong. Instead, we tend to think, feel or say things like, “Well, just because!”

The problem with this sort of morality by mere intuition -- “well, I/everyone just know(s) that y is wrong” -- is that actions once seen as clearly immoral become merely taboo, and as such become vulnerable to charges of bias, prejudice or bigotry. After all, if you can’t articulate why doing y is wrong, then maybe you are just being irrational -- bigoted -- towards those who do y.

Being able to articulate your morality, then, serves (at least) two functions: it acts as a bulwark against holding moral positions where are in fact merely taboos, and it allows you to explain and persuade others as to why doing z is wrong. After all, if we truly love others, then we desire that they avoid immoral actions, both for their own good and the good of others, and hence we ought to seek to convince them of the truth of our moral code, which requires that we be able to articulate that code.

One great way to articulate the rationale for your morality is to ask yourself why (or some similar question) repeatedly -- say, five or six times -- with regard to a particular moral action. And here’s the thing: “Because it just is (or isn’t)” isn’t a legal reply!

Here’s an example:

Stealing is wrong.

Why?

Because you shouldn’t take property that doesn’t belong to you.

Why not?

Because it belongs to them and not to you.

So?

Well, justice means giving to another what is due to them; if you take someone’s property without their permission and/or without compensating them, you are committing an injustice.

So?

Living justly is necessary for the good both of individuals and of society… if you can freely take someone else’s property, then someone else can freely take yours, which leads to “might makes right” as the law of society, which makes life miserable for the vast majority of the members of that society, almost certainly including you.

Warning: you might get stuck! It might take you some time to answer your “why (not)/so what?” question… that actually happened to me as I was working on the example I just gave, after just the second question! But again, it’s worth it… while my intuitive sense might very well be correct -- perhaps stealing isn’t just taboo, but is really wrong -- it’s important to verify that there are real reasons to hold that position.

In addition to asking such a series of questions yourself, it’s also worth asking “Why not?” etc. when talking with others about moral issues, whether they agree with you or not. But: the goal here should never been to merely stump someone else and/or show how much more thoughtful you are than them… the goal is to encourage everyone to think more deeply and clearly about your moral judgments.

Doing so can only be of benefit for ourselves and our communities.

What do you think? How easily do you provide the rationale for your own morality, whether it be to yourself or in conversation with others? Why do you think doing so is so rare in our society today?

Wednesday, July 08, 2015

You keep using that word… I do not think it means what you think it means.

One of the central difficulties which the Church faces in responding to Obergefell is that what most Americans understand marriage to be today is at odds with the historic understanding of marriage, both within and outside Christianity, and hence a substantial renewal of the culture's understanding of marriage is required.

Here’s the thing: both sides in the (yes, ongoing) debate keep using the word marriage, but I don’t think that it means what they think it means…

I subscribe to the magazine Touchstone — “A Journal of Mere Christianity” — and several years ago I read one of the most penetrating, clarifying articles on the state of marriage in American society I’ve come across. Entitled “Phony Matrimony,” I’ve seen similar points made elsewhere, but the insight with which the author of the piece — Christopher Oleson — made his points struck me in a way other similar analysis have not.

Like many others Oleson notes that what passes for marriage in the minds of most Americans is something very different from the conception held just a few generations ago. Like others, Oleson notes that at the heart of the traditional conception of marriage is pro-creation: at a fundamental level, marriage is oriented and structured towards childbearing, even if pro-creation never in fact occurs. And it is because of this intrinsic purpose that marriage is utterly indissoluble. Again, this itself is nothing new: the Catholic Church, for instance, has long taught that the purpose of marital love is for the union of the spouses and the pro-creation of children, and it is from both that the indissolubility of marriage flows.

What struck me about Oleson’s analysis isn’t so much his view of the nature of authentic marriage — again, he largely echoes what others have said — but rather his diagnosis of the conception of marriage which is most commonly held today in our country. Oleson argues that what passes for marriage in this country is more aptly described as “contractually formalized couplehood”. He writes, “We have maintained the term ‘marriage’ as an esteemed and protected word, but what that word once signified has lost its public existence within our culture.” And he proceeds to systematically make his case, first laying out the nature of authentic marriage, then turning to this contractual couplehood which so many of us mistakenly understand as marriage. Noting that the latter is considerably different from the former, Oleson writes,

Whether you’re chatting with Bobos at the nearest Starbucks, listening to conservative talk-show hosts, or attending a wedding at a local Evangelical church, there is a discernable near-unanimity regarding marriage that underlies the public disputes over who can enter into it.

What are these core assumptions that are commonly embraced by mainstream American society, both conservative and liberal? The most commonly recognized ingredients of a marriage are a man and a woman who are in love with each other and want to be with each other for the rest of their lives. They seek a public recognition of that love and commitment. There need be no doubt that most of the time there is complete sincerity on both sides about wanting to make a life-long run of it “till death do us part.”

He then proceeds to point to two other cultural assumptions which place contemporary marriage radically at odds with the more authentic version thereof:

The first is that children are commonly thought to be an attractive but supplementary add-on to a marital relationship. In other words, the intention to have children is not seen as of the essence of what it means for two people to be getting married. Children are considered accidental and posterior to the union.

“Yes, of course we eventually want children. But we’ll decide about all that later.” Or “Having children at some time is attractive to us, but we haven’t made any final decisions about it.” Or simply, “We’re not sure whether or not we want children.” None of these sentiments raises so much as an eyebrow in our society because marriage and the intention to have children are taken to be quite distinct decisions in our cultural outlook.

He then turns to the second constitutive element of traditional marriage, and its status in contemporary conceptions of marriage:

The second cultural assumption has to do with the intentionality with which a couple enters the marital union. Assuredly, they want to be together for life, but if you press deeply enough, you will discover that almost everyone still allows for the (remote and undesired) possibility that, should things not work out, another marriage to a different spouse is still theoretically possible. In other words, there are certain conditions attached to the union. Should the unthinkable happen and one or both of the spouses become miserable with little prospect of amelioration, divorce and re-marriage would be acceptable.

Even if one does not envision this happening to himself, still it is generally taken as a given that others should be able to find a new spouse who, this time, will make them happy. In other words, American society does not regard marriage as an indissoluble relationship. It is a revocable contract and ultimately may be dissolved and then entered into with a new party.

It is true that in almost all circles of American society, there is still a strong sense of the propriety and desirability of lifelong marriage. But the actual belief and frequent practice of mainstream American culture, conservative and liberal alike, is that a “do over” is always possible. Pick a conservative Evangelical church at random out of the phone book. Go visit it, observe its practices, and you will see that it re-marries members of its flock, sometimes repeatedly, albeit recognizing the painful “failure” that resulted in the divorce of the previous and supposedly “Christian” marriage. I’m not saying that this is unfailingly the case. It is only overwhelmingly the case.

And so on, leading to the inexorable conclusion: “When a modern American couple, oblivious as they are to the procreative and indissoluble nature of the marital covenant, goes to the altar or courthouse and commits to living together for life, they are not actually getting married in the original sense of that word. They are entering into a contractually formalized ‘couplehood.'”

To be honest, I can understand the frustration of supporters of same sex marriage in today's debates -- and hence their joy at Obergefell -- and Oleson puts it almost perfectly: “What is the rational difference, after all, between a heterosexual couple who marry with no intention of having children, engage solely in non-procreative sexual activity, and regard their union as dissolvable, on the one hand, and a same-sex couple who marry with no intention of having children, engage solely in non-procreative sexual activity and regard their union as dissolvable?” There is none. If marriage consists of very strong feelings for another, together with some sort of non-procreative sexual relationship and a commitment to stay together, then there is no rational case to be made in opposition to same sex marriage. The obvious problem is that this is exactly what many Americans — most of whom are Christians — believe marriage is!

The renewal of traditional marriage in our country has a longer way to go than many of its supporters probably realize.

What about you? Which sense of marriage do you more commonly identify with, and why?

Sunday, June 28, 2015

Living the Joy of the Gospel in Our Marriages & Families

Every single Christian couple has an opportunity to be a culture-maker, a culture-builder, insofar as they live vibrant, joy-filled, attractive marriages and family lives.

Friday’s Supreme Court ruling in Obergefell v Hodges, which legalized marriage between two people of the same sex across the country provides an opportunity for me to unpack the second facet of Cruciform’s exploration of the intersection of Christianity & culture, namely, culture-building.

In several previous posts I’ve noting the importance of engaging culture by analyzing and assessing cultural “artifacts”: movies, music, books, etc. (See my two posts on Avengers: Age of Ultron as examples.) This is what I’ve referred to as being a “movie critic” in the broad sense of cultural engagement.

But I’ve also noted that cultural engagement isn’t only about assessment and analysis; it’s not just about being a movie critic: it’s also about being a movie maker. And again, that’s meant in the broad sense of forming and shaping culture in all sorts of ways.

One of the most overlooked yet most important ways in which Christians can be “movie makers” in this sense is in our marriages and in our families. The fact of the matter is, most of us have a relatively limited “sphere of control”: beyond the (also underestimated) power of prayer, there is little that most of us can do to make a visible difference in the lives of people with whom we don’t have a relationship: unless we wield significant political, economic or cultural power, our sphere of influence (let alone control) is relatively limited (again, with the power of prayer as an eminently notable exception).

But with those with whom we do have a relationship, and particularly those in our immediate family, our ability to make a difference and to build up a Christian culture significantly increases.

This isn’t something to be neglected. As the old saying goes, the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world: future generations of Americans receive a fundamental formation and understanding of life as they grow and mature in their homes. This means that parents play an incalculable role in setting the course of our society.

But it’s not just as parents of children that men and women are “movie makers”: it’s also simply as husbands and wives. And it’s in both of these roles -- simply as Christian spouses as well as as Christian parents -- that we are called to make a particular difference in this time and in this country.

On Friday the Supreme Court ruled that two people of the same sex can legally marry in any state in this country. As numerous commentators have noted, in so doing they fundamentally changed the definition of marriage, in that hereto for marriage had been understood not only as a deep bond of love between two people, but as a specific kind of bond that was fundamentally ordered towards childbirth and childrearing.

Now, I don’t want to get into the specifics of this argument, although I’m sure that the discussion over same sex “marriage” will continue, just as the debate over legalized abortion goes on more than forty years after the Supreme Court ”decided” that issue as well. I just want to make one point here: while I am writing this post primarily with fellow Christians in mind, remember that the case for traditional marriage can be made in a completely secular fashion, meaning, without any reference to any religious belief, teaching or practice. But that’s a conversation for another post. (In the meantime, read anything by Ryan T. Anderson, like this article from 2013.)

For the purposes of this post, I want to speak to my fellow Christians about what we can do to make a difference, what we can do to build a Christian culture of marriage, about what we can do to bear witness to our faith on this particular issue.

Here’s the answer:

Live a happy, healthy, holy marriage, a marriage that is joyful and joy-filled, a marriage that endures every storm it encounters with a rock-solid confidence and trust that Christ will rebuke the wind and still the seas.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="482"]

Rembrandt, The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 1633[/caption]

Rembrandt, The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 1633[/caption]For while marriage as a legal construct in this country is now open to more, marriage as as societal reality has been suffering in this country for decades, and it’s high time that we start to live in a way that reflects what we believe, about life in general and marriage in particular.

Pope Blessed Paul VI said that for the people of our time the best teachers are witnesses. So if we want to teach our culture about the true meaning of marriage, it’s absolutely essential that we start to live the true meaning of marriage.

For Catholics in particular, we need to live the teaching that marriage is a sacrament, a visible sign by which God communicates his loving, life-giving, healing, saving and amazing grace.

For all of us, do we really believe that what we believe about marriage & grace is really real? Do we really believe that having Christ at the center of our marriages really matters, really makes a difference? How easily could we bear witness to the difference that Christ has made in our marriages?

On Friday Denver’s archdiocesan newspaper, the Denver Catholic, invited Christians to respond to this cultural moment not with despair, but with hopeful excitement:

Jesus Christ is real. We Christians have experienced the sweetness of a personal relationship with Him. Our mission is not to punish or coerce those who have not experienced this—instead, we must invite them into relationship. What better way to do this than to show the joy of living the Catholic faith?

And here’s the thing: it works. Check out the examples in this post, including that of the Catholic author Eve Tushnet, who is attracted to women and yet lives a life of celibacy and embraces Catholic teaching on sexuality. It was the joyful witness of Catholics that lead her from a life of irreligious gay activism to committed Catholicism.

So, start praying as a couple, as a family, for the grace of a joyful marriage, that you might bear witness to the difference Jesus Christ makes in your own home. That’s a prayer that God will surely answer, and when He gives that grace we cooperate with it… fruit will be born, thirty, sixty… even one hundredfold.

How will you answer this call? What are the steps that you will take to live a marriage of joy that bears witness to your faith?

Monday, June 22, 2015

Let Not Your Hearts Be Troubled

Among the many gifts of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, one which is it greatest need in our world today this this: the gift of peace. For despite the great power we possess, power which allows us to order and control so much of our life, we still recognize that that power has limits, and with that recognition comes worry, fear and anxiety.

Into that world comes Jesus Christ, Who says to us what He said to His Apostles one week after the Resurrection: "Peace be with you."

In this post I’d like to briefly sketch the anxiety of our age and its antidote: the Peace of Jesus Christ that surpasses all understanding.

A few years back I came across a short-lived cable show devoted to the incredibly-extensive underground shelters which some people (“preppers”) were having built to protect them from whatever apocalypse they thought was on its way. I was struck by the elaborate nature of these shelters… many of them were as well furnished as my own home! And given the fact that they were buried underground and were built to survive extreme climate & environmental changes, they were also incredibly expensive.

Then just a few months ago I came across something which topped those shelters: the Survival Condo: luxury condominiums built in a repurposed missile silo to allow their owners to survive the collapse of civilization as we know it.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="462"]

The Survival Condo[/caption]

The Survival Condo[/caption]Here’s a summary:

The Survival Condo is an engineering marvel designed for comfortable long-term survival in a former Atlas missile silo. It offers spacious condos with many amenities including luxury living space and a community swimming pool, dog walking park, rock climbing wall, theater, general store and an aquaponic farm, among other features, all of which are underground and encompassed by walls that are 2.5 – 9 feet thick. A half-floor unit is ~900 square feet and runs $1.5 million. The full floor version costs $3 million for 1820 square feet.

As the official website for this project indicates, the first silo is sold out, and units in a second silo are going fast.

Meaning, tens of millions of dollars are being spent by people looking to survive the end of the world as we know it.

Meaning, there are multimillionaires who are truly putting their money in a (huge) hole in the ground.

The Survival Condo and other efforts like it are a dramatic sign of something widespread in our culture: our desire to control every aspect of our lives that we possibly can, to anticipate and even avoid every bad thing that might happen. The Survival Condo is a very real, very large and very expensive manifestation of the great anxiety of our age.

The scope of our cultural anxiety really is astounding. Consider, after all, the incredible material wealth that even the average middle-class American enjoys and then consider how much we worry and fret about it! Or think about our health: while millions of people in the world struggle to get enough to eat, our problem is just the opposite: we eat too much! Despite that, however, our medical technologies still give us lifespans into the eighth decade on average, and yet we worry and fret about our health, we seek to manage and control it so that we can live just a few more years.

In all of this, we see an extraordinary lack of the thing which was heralded by the angels at the birth of Christ, the thing which He gave the Apostles after the Resurrection: His Peace, Peace on Earth, Peace in our hearts, and the calm and trust that it entails.

As our experience indicates all too well, we cannot achieve, accomplish or manufacture that deep peace that we long and yearn for. But that’s okay… we don’t need to: Christ desires to give it to us, freely.

All we have to do is accept it, all we have to do is trust Him, all we have to do is know that everything that might happen to us has been accounted for by our Heavenly Father, and that whatever pain & suffering we experience -- including death -- is not the last word, that despite it, He will (and already does!) envelop us in His loving embrace.

No, we cannot achieve peace. But we can receive it. And here's the thing: many of us have.

So why is it still so hard to do so?

Thursday, June 18, 2015

The Goal of Christian Morality: Our Happiness!

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="365"]

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Saint Teresa in Ecastasy, 1647-52[/caption]

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Saint Teresa in Ecastasy, 1647-52[/caption]One of my favorite topics in moral theology is the the place of happiness in Catholic moral thought, and in this post I want to dive a little more deeply than normal into some theology, but bear with me...

There is an unfortunate tendency today among many -- even among some committed Christians -- to believe that Christian moral norms are apparently arbitrary whims imposed on us by God and/or by our Church leadership.

There is actually a good deal of truth to this belief, in that there has been a long history in moral theology of focusing on the "willed" aspect of moral norms, i.e. that things like the Ten Commandments are willed by God, and therefore we ought to obey them for that reason. This perspective began primarily with John Duns Scotus in the High Middle Ages and continued through William of Ockham in the Late Middle Ages. It was via Ockham and his circle that this voluntaristic emphasis, focusing on the will, spread during the Reformation, and in the Counter-Reformation and succeeding centuries many Catholic moral theologians continued to hold to this emphasis, as seen in what’s called the "manual tradition" of moral theology in the first half of the twentieth century.

Now, I would certainly agree that we ought to follow God's will; I definitely have no issue with obedience. The problem comes in when God's will is made to appear arbitrary, i.e. there is no attempt to discover the divine rationality behind His moral precepts. In fact, some would posit that we even shouldn't make such an attempt, that it is wrong to do so.

What this leads to among too many believers is a Christian "moral spirituality" which undertakes Christian moral precepts as if they were a great weight which must simply be carried: ours is not to wonder why, ours is but to do and die. I am a Christian, and therefore I have to "put up" with these precepts. For the non-Christian looking in, there is little to find which is attractive in this atmosphere. It appears laden with legalistic norms which lead only to misery in this life, with the promise for (eventual) happiness in the next.

Such a picture is not only depressing, but need not -- nay, should not -- be the portrait painted by Christian moral theology and practice. Furthermore, it is a perspective which is relatively new -- as noted above, it was only in the High Middle Ages that this understanding of morality really began. Before that -- and ever since, among a school which was in the minority of moral theologians for far too long -- Catholic moral theology saw another divine purpose in living a moral lifestyle: authentic, real happiness.

St. Augustine opened his treatise on Christian ethics ("The Standards of the Catholic Church") with the following words: "There is no doubt about it. We all want to be happy. Everyone will agree with me, before the words are even out of my mouth. [...] So let us see if we can find the best way to achieve it." As the noted Dominican moral theologian, Servais Pinckaers, commented, "For Augustine, morality begins with the question of happiness -- authentic happiness -- and consists entirely in finding an answer to this spontaneous, universal question. Morality is a search for happiness" (emphasis added).

As Pinckaers goes on to note, this perspective was obvious to Augustine, but is very foreign to most of us (Christian or not) today. As he says, "we are used to thinking of morality from the viewpoint of obligations and prohibitions. We equate it with a body of teaching about commandments and sins, and do not readily perceive how it connects with our desire for happiness. In fact, the two things seem contradictory” (emphasis added).

Isn't this true? Don't most of us see morality and happiness as opposites, or at least understand them so in an unconscious manner?

As we see above, though, this was not how St. Augustine understood happiness, and his perspective was held by most theologians into the High Middle Ages, including his most famous disciple, St. Thomas Aquinas, who was described by one of my Angelicum professors as being "more Augustinian than Augustine was."

For St. Thomas, like Augustine, a moral life is the path to authentic happiness. Yes, there may be initial "pain" as we begin to live the life of virtue rather than vice, but in the end, the happiness we will have through the grace of God and the life of virtue will far outweigh whatever pseudo-happiness we may experience otherwise.

This "take" on morality is once again taking its rightful place, through the work of men like Servais Pinckaers (I would recommend his reflections on the Beatitudes, The Pursuit of Happiness -- God's Way, from which the above quotes were taken, and his more scholarly work, The Sources of Christian Ethics). Yes, we must follow God's will, but we must remember and emphasize to others that God wills our happiness, and therefore that living the moral life will lead us to that end of real happiness, in this life and the next.

Living the Christian life should not be a burden to us; as Jesus said, "my yoke is easy, and my burden is light" (Mt 11:30). When we realize that God desires our happiness, and that living the life He sets before us will lead us there, Christian morality is transformed for us and for others.

What about you? Have you seen Christian morality as the path to happiness, or as a heavy burden, or as something else?

Tuesday, June 16, 2015

Why Do You Persecute Me?

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="434"]

Caravaggio, Conversion on the Way to Damascus, 1601[/caption]

Caravaggio, Conversion on the Way to Damascus, 1601[/caption]One of the most compelling Scripture passages is found in chapter 9 of the Acts of the Apostles: the conversion of St. Paul on the road to Damascus. Among the many fascinating aspects of this narrative is the connection Jesus makes between Himself and His Church. His first words to Paul are, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” and when Paul asks who He is, Jesus replies, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting.”

Obviously, Paul was not literally persecuting Jesus, in that He had already ascended into Heaven. However, he was persecuting Jesus’ community of disciples, and so from Jesus’ words to Paul, we find a certain kind of identity between Jesus Himself and His Church, to such a degree that to attack the one (the community of disciples) is to attack the other (Jesus Himself).

This “secondary” aspect of St. Paul’s conversion clearly had a deep effect on his understanding of the Church, in that he is the primary Scripture writer who refers to the Church as the “Body of Christ”. We can rightly infer that this understanding of the Church derived from his conversion experience.

What this means for us is important: we cannot view the Church as some sort of “third thing” that comes between the disciple of Jesus and Jesus Himself. Rather, the Church is the very place wherein we encounter our Risen Lord, in that the Church is in some mysterious yet real sense the Body of Christ. We can no more be an authentic disciple of Jesus and exist outside the Church than an arm can continue to exist after it has been cut off from the body.

Furthermore, this also shows us that the Church is more than a “coming together” of disciples, that the Church does not come to be only when disciples gather. Rather, the Church – as the Body of Christ – in a certain sense “pre-exists” individual believers. So when someone is converted to Our Lord, they are “grafted into” His Body and become a living member thereof by joining the already-existing Church.

To me, this sort of thing shows the depth underlying Sacred Scripture. What seems fairly innocuous at first reveals great depth on closer inspection. As Pope St. Gregory the Great once said, Scripture is shallow enough for babes to swim in and deep enough for an elephant to drown in.

What about you? How do Jesus' words to Saul on the road to Damascus -- and what that means about the Church -- strike you?

Sunday, June 14, 2015

Bruce/Caitlyn Jenner and What It Means to Be Human

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="716"]

.jpg) Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam, 1511-1512[/caption]

Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam, 1511-1512[/caption]If one of the central purposes of Cruciform is to offer a Christian perspective on (American) culture, I suppose it’s time I wade into the cultural issue of the day: Bruce/Caitlyn Jenner.

Actually, I’m not going to comment directly on Jenner himself. Instead, I want to look a bit deeper at what his attempted change in sex from man to woman and the discussion it’s generated means about how we answer this question today: what does it mean to be human?

Like others who identify as transgendered, Jenner has stated that he has always felt like he was really a woman, that whatever the state of his body, on the inside he wasn’t a man.

Implicit within this perspective is an understanding of what it means to be human, and specifically, of what the essence of the human being is, which is thousands of years old and which has cropped up in numerous religious and philosophical systems, from versions of ancient greek philosophy to today’s New Age spiritualities. This perspective is technically referred to as body-self dualism, and essentially it sees the “self” -- the person, the source of worth and dignity in the human being -- as distinct from the body.

In other words, body-self dualism understands the body not to be truly personal; instead, the body is merely a means, a tool which the person dwells (or is entrapped) in. The human body, in this understanding, is merely sub-personal.

For a variety of reasons, body-self dualism is ultimately a false understanding of the human person. But my purpose in this post isn’t to engage in a deep study of the philosphical arguments against body-self dualism (for that purpose, I’ll refer you to this article by Patrick Lee and Robert George). Instead, I want to focus on the theological issues which it raises.

Now, most people -- probably even most Christians -- might initially think that Christianity holds to a body-self dualism. After all, Christians believe that the human being is composed of both body and soul, and that while the body will die, the soul will exist forever.

In fact, however, any similarities between traditional Christianity and body-self dualism are only superficial, and beneath those similarities lie profound and ultimately irreconcilable differences. Let me explain.

Yes, it’s true that Christianity holds a form of dualism: the human person consists of both body and soul. But there is a key distinction: Christian dualism is body-soul dualism, not body-self dualism. And those three letters -- -oul vs. -elf -- make all the difference.

For Christianity, the “self” -- the person -- is not the soul by itself, in or out of the body. Rather, for Christianity, the human person, the “self”, is actually the union of the body and soul, the composite of the body and soul. Contrary to one popular opinion, Christianity doesn’t denigrate the body, but just the opposite: it elevates it, given it the status and dignity of human personhood. While body-self dualism sees the body as merely an instrument of that which has real and intrinsic value (the self), Christianity sees the body as having inherent and intrinsic value, precisely because it is one part of the union that together makes up the human person.

For me as a Christian, then, it’s technically imprecise for me to say that I have a body… it would be more accurate to say that I am a body, or even more precisely, to say that I am a body-soul composite.

The difference here with body-self dualism is substantial, for while body-self dualism says that the person is some immaterial, non-physical (presumably spiritual) reality, Christianity instead says that the person is the unity of the body and soul together.

This actually manifests itself out in everyday life. Think about our ordinary language; we say things like “Did you see that sunrise this morning?” or “I heard the most amazing song today!”. Note what we don’t say: we don’t say, “Did your eyes see that sunrise this morning?” or “My ears heard the most amazing song today!” Our ordinary way of speaking itself implies an understanding of the human person as one of a profound unity between the matter and spirit, not of a strong dualism between them.

This is why it is is deeply problematic from a Christian perspective to argue that my “real self,” the “real ‘I’” is one sex and my body is another, because it presumes that my person, my self, is something other than my body, while for Christianity, my person, my self essentially includes my body. For Christianity, there is no “I’ that is “inside” my body… the “I” is my body, united as it is with my soul.

Ironically, the extremely high value which Christianity places on the body is the source of many of the doctrines which many Americans are uncomfortable with. Abortion… contraception… man-woman marriage… euthanasia and yes… transgender issues… it is precisely because Christianity so highly values the body that it teaches what it does on these issues (for more on this, I’d recommend another Robert George article).

It’s essential that we walk with, pray for, support and love those who struggle with their sexual identity. And in doing so, we can be confident in assuring them that not only we, but God Himself is with them as they carry their cross, and that the ultimate end of their personal Way of the Cross is not Calvary, but the Resurrection.

Thoughts? In what ways does this post confirm your understanding of the human person and/or of the Christian understanding of the human person?

Tuesday, June 09, 2015

Communicating in an Age of Distraction

The Light Phone[/caption]

The Light Phone[/caption]We’ve now come to a place where what we once called “dumb phones” are heralded as a technological advance and novelty.

A few weeks back I came across this article about a new phone called “The Light Phone,” a cell phone that is lasts for an incredible 20 days on one charge. But that’s not what’s most notable about the Light Phone; what is most notable about the Light Phone is that you can do one thing and one thing only on it: have a phone conversation.

The Light Phone, in other words, is a dumb phone, and frankly, it’s even dumber than dumb phones, because you can’t even text with it! No apps, no mobile web browser, no music… just. a. phone.

Yet despite its dumbness, this phone has raised over $360,000 in its Kickstarter campaign, with 18 days still to go.

Apparently there’s at least something of a market for dumb phones.

I’m deeply intrigued by the Light Phone and the positive response it’s received over a year before it’s even available. It reflects an interesting dichotomy in our society: one the one hand, we love our gadgets and all they can do. Stop and think about our smartphones for a minute; they truly are an amazing feat of technology that allows us to do things “on the go” that were impossible just ten, fifteen years ago.

But on the other hand… we dislike -- even hate? -- our gadgets and all they can do, or at least some aspects of them. In particular, we hate their ability to distract us. As my family friends and colleagues can tell you, I check my phone almost compulsively now… looking to see if I’ve received any emails, text messages, Facebook notifications or comments here on Cruciform.

And I hate it.

I hate the fact that I cannot just be present to those I’m with, that I can’t set my phone aside -- or even turn if off! (gasp!) -- for an hour to talk with someone.

Hence, things like the Light Phone: advances in technology that purposely have fewer capabilities than their predecessors.

What does that say about our culture, that we need to turn to technology to solve problems that technology itself has created? Or more, what does it say about me that I can’t leave my phone alone while in the middle of a conversation?

I’m not sure how to answer those questions myself, other than to say… I don’t like it.

Oh: and that I need to pray for the virtue of temperance! (Yes, temperance, specifically its daughter, studiousness.)

What do you think? Is there really anything wrong with our technology-enhanced propensity to distraction? If so… what?

Sunday, May 31, 2015

We're Not Worthy, We're Not Worthy!

Despite the title of this post and the image above, this is not a post about Wayne or Garth, but rather one that continues the discussion begun in last Monday’s post on Avengers: Age of Ultron.

As I mentioned in that post and in other posts on Christianity & culture, one of my goals with Cruciform is to occasionally offer examples of engaging culture by thinking deeply about the presumptions, messages and questions-posed by the music, movies and other cultural artifacts we encounter. This is what I call playing “movie critic” (as opposed to “movie maker,” i.e. cultural engagement by creating new culture).

In last week's post I looked at some of the more subtle philosophies presented in Avengers. In this post, I’d like to look at one of the more humorous plot points in this blockbuster and its implications…

****(Spoiler Alert! If you haven’t seen the film and don’t like having your surprises spoiled, stop reading this post now!)****

One of central characters in the movie is Thor, currently portrayed in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) by actor Chris Hemsworth. Both in Marvel Comics and in the MCU, the character Thor is “based on the Norse mythological deity of the same name, is the Asgardian god of thunder and possesses the enchanted hammer Mjolnir.”

In the 2011 film Thor -- in which we are introduced to Thor as portrayed in the MCU -- Thor is stripped of his godly power by his father Odin because of his arrogance. Not only that, but he is additionally exiled to earth along with his hammer Mjolnir, which is now only able to be wielded by the worthy (in Marvel comics, the inscription "Whosoever holds this hammer, if he be worthy, shall possess the power of Thor” is inscribed on the side of Mjolnir). In the course of the film, through an act of self-sacrifice for the sake of others Thor does indeed become worthy, and at a critical moment he regains his godly powers and is once again able to wield Mjolnir.

The inability of anyone unworthy to wield the hammer thus becomes a recurring theme throughout the Thor and Avenger films. In the early stages of Avengers: Age of Ultron, one of the more humorous scenes finds each of the other Avengers attempting -- without success -- to pick up the hammer, with a smirking Thor looking on, indicating that they are apparently unworthy. (At one point, the smirk disappears when Captain America manages to budge Mjolnir ever so slightly.) And then late in the film, all of the Avengers -- including Thor -- are shocked to see one of the new characters in the film (The Vision) nonchalantly carrying Mjolnir, indicating that he is in fact worthy to wield the mighty hammer.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="655"]

Thor's smirk disappears as Captain America budges Mjolnir.[/caption]

Thor's smirk disappears as Captain America budges Mjolnir.[/caption]What struck me about this plot point and what I’d like to explore in this post is the notion of worthiness as it is implicitly understood in Ultron and in the other films of the MCU.

I’m struck by the MCU’s notion of worthiness because it’s a concept which is is many ways outmoded in our culture. In our society today, the idea that I might be morally unworthy to do something is incomprehensible and even offensive. Ours is a culture dominated by what Mary Ann Glendon of Harvard Law School calls “rights talk”: “It’s my right to do X,” “Who are you to deny me the right to Y,” etc. It’s as though we have a moral right to virtually everything. Not only that, but we are similarly repulsed by the idea that when it comes to someone’s morality, someone’s character, that there is any “better,” any worthy or unworthy.

And so here comes Thor, with his British accent (aristocracy, social hierarchy, etc.) and his judgmental hammer.

And yet… we do not disagree, we are not offended, we do not take umbrage at the fact that not Iron Man, not Hawkeye, not War Machine, not even Captain America can lift Mjolnir. Why? Because at a fundamental level, we recognize the fallacy of our culture’s exaggerated egalitarianism, of the claim that we are all morally the same. In short, we recognize that some are more virtuous than others. Or to make it more personal… I, Chris, recognize that there are people who are better than me, not just athletically or intellectually, but morally better than me. My culture can tell me all it wants that I’m just as good as anyone else, but deep in my bones I know that that’s not true, I know that there are men and women who live lives of greater virtue than me.

And here’s a final note: in the end, the only characters who are able to wield Mjolnir are a Norse god and a character who, when asked his name, replies “I am… ‘I AM…,’” the name by which the God of Israel reveals Himself to Moses in the Burning Bush in Exodus 3:14 (“Say this to the people of Israel, ‘I AM has sent me to you’”).

In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, then, we find an idea which is both deeply Christian and deeply subversive of a dominant cultural narrative.

And we accept it.

What do you think? Why is it that we struggle in real-life with the idea that some are more or less worthy than others?

Tuesday, May 26, 2015

The Simplicity of a Child

Back in 2002 then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (elected Pope Benedict XVI in 2005) published his three book-length interview, God and the World, his second such work with the German journalist Peter Seewald.

Despite the fact that the book is thirteen years old and that Ratzinger/Benedict is now living out the remainder of his life essentially out of the public eye, the interview remains a powerful text, worthy of consideration and reflection. In this post, I’d like to highlight one excerpt that relates to recent posts here at Cruciform.

Seewald asks the Cardinal about Jesus' enthusiastic love for children, and quotes Matthew 11:25: "I thank thee, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, that thou hast hidden these things from the wise and understanding and revealed them to babes." Ratzinger comments thusly:

Yes, here again is the mysterious pattern of the way God acts: the whole magnitude of it is more easily grasped by simple people than by those who, with a thousand distinctions and diverse intellectual baggage, ferret out each little bit on its own and are no longer capable of being overwhelmed by the magnitude of the whole.

No rejection of intellectuals, or of detailed knowledge of Scripture, is intended here, but a warning not to lose our inward simplicity, to keep the meaning of the whole in view, and to allow oneself to be impressed, to be ready to accept the unexpected.

It's no secret that for intellectuals this is a great temptation. When we look back on the history of the ideologies of the past century, we can see that simple people have often judged more soundly than intellectuals. The latter always want to make more distinctions, to find out more about this and that--and thereby they lose their overall view. [emphasis added; pp. 243-244]

Ratzinger is right on here. For those of us whose way of living and grasping the faith is perhaps more intellectual, the temptation to over-intellectualize the faith is indeed great. We must always seek to have that childlike simplicity, that awe and wonder at God's work of creation and redemption. We must be on guard against the temptation to "experiment on God," to reduce Him to a scientific project or hypothesis which we are seeking to validate. We must remember that we are the creation, and He is the Creator.

As the Cardinal notes, Jesus is not condemning intellectuals or an intellectual approach to Him per se, but rather He is calling us to retain that wonder, that simplicity, which so characterizes the child's view of the world around him.

How do you maintain the simplicity and wonder of a child in your own faith life?

Sunday, May 24, 2015

Cultural Case Study: Avengers: Age of Ultron

Theatrical release poster[/caption]

Theatrical release poster[/caption]Two things up front: first, this is going to be a messy post. Second, I’m hoping that a good discussion in the comments will enhance the post and perhaps even make the entire thing -- post and comments together -- somewhat less messy.

Let’s begin.

As stated in recent posts and as implied in the subtitle of this blog (“Exploring the Intersection of Christianity and Culture”), one of my central purposes for Cruciform is to consider how we can engage culture in two ways: by evaluating the culture in which we find ourselves, and by creating new culture. Or to use a metaphor: to be a “movie critic” or a “movie maker”.

In this post I’d like to engage in the first form of cultural engagement (“movie critic”) in a more literal sense by looking at the last Marvel Studio’s blockbuster movie Avengers: Age of Ultron.

If you haven’t yet seen Avengers but are planning to, you’d better stop reading now, as this post will require revealing some of the plot details of the movie. If you haven’t seen it -- or don’t mind reading spoilers beforehand and want to have a better idea of what I’m talking about -- you can find a plot summary of the movie at its Wikipedia entry.

Now… how do we play “movie critic”?

First, the quotation marks around “movie critic” are a reminder that the sort of cultural engagement I’m after here isn’t about attempting to be a movie critic in the Siskel & Ebert sense; I’m not a trained movie critic, nor do I play one on tv. When it comes to formal movie criticism, there are plenty of great options out there (my favorite is Steven Greydanus, because he’s both a movie critic and a “movie critic”; you can find his review of Avengers here).

The sort of “criticism” that I’m after here doesn’t require having taking a course in film studies, let alone cinematography… I’m talking about looking more deeply at a piece of culture (a cultural artifact)... at what it’s telling us, both deliberately and accidentally… at what its creator presumes and assumes about our world… at the questions it wants us to ask… at what is true, good & beautiful about it, as well as what is wrong, evil & ugly about it. Rest assured, every cultural artifact -- every movie, every song, every painting, every piece of writing -- does all of these things, well or poorly, and regardless of whether or not its creator intends it.

This sort of criticism, then, requires “only” that we think deeply about the artifact in question (in this case, the second Avengers movie). I put “only” in quotes because while this sort of thought isn’t complicated in principle, it takes practice to perfect, and hence time as well. But it doesn’t require any specialized knowledge about movie making, painting or poetry… it only requires reflection and thought.

One of my favorite “movie critics” in this sense is Fr. Robert Barron, a priest of the Archdiocese of Chicago, and rector of the seminary for the Archdiocese (a seminary rector is the priest appointed by the bishop of that diocese to run the seminary on his behalf). Fr. Barron is a terrific theologian who has been writing great books for many years, but he first popped onto the radar of many Catholics several years ago when he started posting videos on YouTube in which he’d offer his thoughts on popular movies and books along the lines I’ve sketched here… you can find those videos on his YouTube channel here or collected in written form in his recent book, Seeds of the Word, and you can find his “movie critic” take on Avengers here.

Now that I’ve explained what it means to be a “movie critic”, let’s test it out by looking a bit more closely at this summer blockbuster. But note: I’m only going to introduce this here… I’m hoping that we can play “movie critic” together in the comments. So, let’s dip our feet in...

One of the things that struck me about the movie the amount of “God talk”, as Greydanus describes it, and the implicit Catholic references. This isn’t shocking, given that director Joss Whedon has been noted for raising spiritual questions, for Catholic allusions, and for subtle advances of his atheism in his previous works. But it did surprise me because similar references and themes were mostly absent from the first Avengers movie, also directed by Whedon.

So what do we make of that? Fr. Barron is fairly critical, seeing in the movie a promotion of a decidedly anti-biblical view of life, one more in line with the thought of the 19th century german atheistic philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

Nietzsche is famous for -- among other things -- his assertion that “God is dead”. Popularized in the 1960’s -- decades after Nietzsche’s death -- for Nietzsche the slogan had far more significance than merely a defiant assertion of atheism; he knew that without God, nothing has meaning or value, and hence he was far more consistent than the “New Atheists” of our day. And Fr. Barron is on solid ground for seeing Nietzschean undertones in the film, given that in the movie Ultron himself utters Nietzsche’s other famous line: “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”.

But one might argue that the film itself is not actually promoting Nietzsche’s philosophy, but merely portraying it. After all, as Fr. Barron notes in the final paragraph of his analysis, we see clearly in Avengers that the Nietzschean approach of Ultron -- and perhaps even of our heroes -- doesn’t actually work, but it only makes things worse. Ultron himself -- the villian of the film, in case that wasn’t clear -- was the creation of Tony Stark (aka Iron Man), who sought to take into his own hands the protection of the planet. Stark sought -- to quote him from the movie, alluding to Neville Chamberlain’s famous line -- to secure “peace in our time”. And yet Stark’s Nietzschean overreach -- trying to achieve by sheer force of will something which we simply cannot achieve on our own -- almost resulted in the very opposite: the destruction of humanity. So one might say that Avengers is in fact anti-Nietzschean at its heart.

This strikes me as typical of highly effective storytellers like Whedon: while he himself is an atheist and that atheism does make its way into his stories, those stories -- because they are in many ways so well crafted -- end up making points that are contrary to his atheism. That is, despite himself, Whedon’s movies include themes opposed to his own principles. (I find the same thing to be true about Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, but that’s for another time.)

Again, those are just a few thoughts that come to mind as I try to play “movie critic” with Avengers: Age of Ultron. You'll note that I haven't yet rendered any judgments about the message of the movie... I don't want to tip my hand at this point. So...

What about you? What do you see as the message, premises and assumptions present in Avengers: Age of Ultron?

Thursday, May 21, 2015

The Taste for Beauty

A few weeks ago I came across a fascinating post by Fr. Dwight Longenecker entitled “Why You Need Poetry”.

Now, I have to confess: I’m not into poetry. And that’s not for lack of trying… I was exposed to it in school, and many an article like Fr. Dwight’s has prompted me to try to get into it.

But so far, no luck.

And yet, I’ll keep trying, for reasons like those spelled out by Father in his post. For I know that there’s a “muscle” in my spirit that is in danger of atrophying: it’s my aesthetic sense, my ability to delight in things, to recognize not only the truth or goodness of things, but their beauty as well, my ability to be in awe of a piece of beautiful music, of a compelling story, of… a poem.

There are all sorts of reasons why this sense is one that I cannot let atrophy any further, why it’s important that I foster my aesthetic sensibility, my taste for beauty, and in future posts I expect to detail and explain those reasons.

For for now, I’ll mention two: first, as I’ve mentioned previously, I want to be more discriminating, more critical in how I consume what our culture offers us, and to do so requires that I strengthen that taste for beauty, that I develop a more discerning palate, if you will.

And second: God delights in my delight. He delights when I am awed by beauty, whether it be the beauty of His creation or the beauty created by His creatures.

And that fact -- that God delights in my delight -- is itself something that I am in awe of.

Tuesday, May 19, 2015

Sin is Stupid (But Maybe Not in the Way You Think It Is)

Something I've realized over the last several years is that people who are not very familiar with the Christian (specifically Catholic) tradition on sin -- and this includes both Catholics and other Christians -- tend to associate belief in sin with backward, repressive, irrational thinking. In other words, to seriously call something "sinful" implies that you are irrational and backward, that you are restricting yourself from achieving happiness by submitting to an apparently arbitrary and irrational moral code.

What is somewhat ironic about this is that in the classic Catholic teaching, sin itself is what is irrational. Note the definition of sin as found in paragraph 1849 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

Sin is an offense against reason, truth, and right conscience; it is failure in genuine love for God and neighbor caused by a perverse attachment to certain goods. It wounds the nature of man and injures human solidarity. It has been defined as "an utterance, a deed, or a desire contrary to the eternal law."

Sin is defined as first being an offense against -- what? -- reason. According to the Catechism, a sinful act is an act against right reason, i.e. it is an irrational act. This same idea was taught by St. Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century; Thomas wrote in his Summa Theologiae that -- among other things -- sin is "contrary to reason" (I-II, Q. 71, A. 6). This understanding of sin is aptly explained by the 20th century german philosopher Joseph Pieper in his book, The Concept of Sin. Pieper also shows how -- again, according to long-standing Catholic thought -- a sinful act goes against our nature. In other words, to commit a sin is to in some way deny or prevent the fulfillment of what it is to be human.

So, contrary to widespread intuitions today, to believe in sin is not to be irrational, but in fact to commit sin is irrational. This furthermore means that one can discuss the sinful character of particular actions in the context of public policy discussions, because this sinful character can also be considered the irrational character of such actions. I'm not advocating using the word "sin" in this sort of format -- precisely because of the common misunderstanding of its meaning -- but rather I am arguing against a tendency to throw out arguments because they discuss acts in terms of sin "instead of" reason. In fact -- as I have shown above -- sins are by definition irrational, and this feature allows us to make arguments against such acts that can't be dismissed by categorizing them as "arguments from sin".

How might this understanding of sin change how you discuss this topic with others?

Monday, May 18, 2015

"Why?"

Seriously.

This might seem to some to be obviously false, given that plenty of people question Church teaching. But I’m not talking about questioning Church teaching in the sense of doubting it; yes, Catholics who disagree with Church teaching (i.e. dissenters) do that aplenty, but what they don’t do is ask “Why?” with sufficient depth, with the goal of truly seeking to understand what the Church teaches on topic X and why she teaches that. In the case of most dissenters I’ve encountered, their “why?” is unfortunately something more like “Well, that’s silly, I don’t believe that,” without any substantial engagement with the Church’s teaching, without any grappling with the inner rationale of the doctrine.

For all of us, there are two ways ask “why?”. One looks like this:

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="232"]

Auguste Rodin, The Thinker, 1904[/caption]

Auguste Rodin, The Thinker, 1904[/caption]The other looks like this:

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="240"]

"Whyyyyy?!?!"[/caption]

"Whyyyyy?!?!"[/caption]And all of us are called to ask it in the first sense.

Remember the greatest commandment: love God with your whole heart, mind and soul. As our everyday experience of love indicates, you can’t love what you don’t know, and you can’t grow deeper in love without growing deeper in knowledge. We are called to grow deeper in knowledge of Church teaching not merely so that we have a greater intellectual grasp of our Catholic beliefs — although that is certainly essential — but so that we can grow in our love for God, so that we can grow as disciples of Jesus Christ.

Catholic doctrine isn’t mere abstract theological mental gymnastics… it matters to my life, to our life, to the life of each and every human being. There is no doubt that there is great intellectual depth to Church teaching, but we cannot forget that those teachings have a real impact — or ought to have a real impact — on our existence.

The evangelization efforts of many Catholics today are focused on demonstrating the truth and rationality of Catholic teaching, and rightly so. But we cannot stop at a demonstration of the truth of Catholicism… we need to show its relevance as well. I’m not saying — as some do — that we need to make it relevant… it already is relevant. Just as we are called not to make doctrine true but to reveal its truth, so too are we called not to make Christianity relevant but to reveal its relevance. There are all sorts of truths which have little or no bearing on my life: the atomic weight of iridium, for example, matters little to my day-to-day existence.

The truths of Christianity, however, are far different. Despite the fact that Church teaching can seem abstract and overly-intellectual, the reality is that these truths do speak to our daily existence, if we allow them to.

We need to be encouraging ourselves and our fellow Catholics and other Christians to ask “Why?” even more, not less. The more we know, the more we can love.

Thursday, May 14, 2015

Yes, a Personal Relationship

Divine Mercy image[/caption]

Divine Mercy image[/caption]“The Christian faith is not only a matter of believing that certain things are true, but is above all a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.” As I’ve said often when giving presentations on discipleship, this quote doesn’t come from Billy Graham, but from Benedict XVI, Joseph Ratzinger, the brilliant German theologian not given to flights of rhetorical fancy.

While this sort of language is foreign to many Catholics, as this quote illustrates, it’s not foreign to our popes; similar statements from Benedict and both his predecessor and successor could be multiplied. One more from Benedict will suffice for this post:

“Being Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction” (God is Love, 1).

As this Easter Season draws to a close, may we grow closer to the Risen One who lives in our midst: Jesus of Nazareth, alive and present in the midst of the community of His disciples. May He open our eyes that we might see Him and embrace Him.

Wednesday, May 13, 2015

Scandals and Sanctity

And yet, the solution is the same: sanctity.

Back in 2002, in the midst of the uproar over the priestly sex abuse scandal in the United States, now-deceased Msgr. Lorenzo Albacete told journalist Michael Sean Winters this:

If, in addition to all the terrible things we have learned, if tomorrow it was revealed that the pope had a harem, that all the cardinals had made money on Enron stock and were involved in Internet porno, then the situation of the Church today would be similar to the situation of the Church in the late twelfth century ... when Francis of Assisi first kissed a leper.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="468"]

Saint Francis and the Leper, Santuario di San Francesco, Greccio, Italy[/caption]

Saint Francis and the Leper, Santuario di San Francesco, Greccio, Italy[/caption]Not only does this quote give some perspective to how bad things have been at various points in the Church's history (and how things today are far from the worst), it points to the solution: saints. Commenting on Msgr. Albacete’s words at the time, Fr. Richard Neuhaus in turn said this: "In short, the Church will only be renewed by saints, meaning sinners -- bishops, priests, and all the faithful -- responding to the universal call to holiness."

Don't just Be Happy. Be Holy.

Why Not?

Monday, May 11, 2015

Critical Cultural Consumption

I alluded to this struggle in my last post when I referred to two of the ways that we as Christians can engage the culture: by evaluating existing culture and by creating new culture, or, to use the image I proposed at the end of the post, by being a “movie critic” or a “movie maker”. As I mentioned there, being a “movie critic” entails that “sifting” process of separating the wheat from the chaff, the good from the bad, the beautiful from the ugly, the true from the false when we engage or even simply “consume” things in our culture.

I know that leaving the bad, false & ugly is necessary… consuming everything the culture offers me without any thought or discernment is like eating without paying any attention to the nutritional value of the food.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="245"]

Theatrical Poster[/caption]

Theatrical Poster[/caption]And while the monastic or Amish approach -- leaving the world behind almost completely and consuming almost nothing from the wider culture whatsoever -- might work for some, I think most of us are called to be what’s in the title of the previous post: in the world, but not of the world. That’s where the level -- or better, manner -- of engagement becomes a bit trickier to get right.

As I said, this is a balance I can struggle to get right… this will be one of the recurring Culture topics here at Cruciform. But in the meantime, I’d love to hear any thoughts that any of you might have: how do you maintain that balance in your own life?

Tuesday, May 05, 2015

In the World But Not of the World

The mission which Jesus has given to all members of the Church -- and to the lay faithful in a particular way -- entails being in the world but not of the world (cf. John 17:15-16). As lay Christians, we are called to engage the culture in which we live -- or more accurately, the variety of cultures in which we live -- in order to transform them.

This means that we, as Christians, must determine how to best and most effectively engage the culture in which we live, how to make a difference in the lives of those around us, in the places not only where we live but where we work, shop and recreate. We are called, in other words, to be engaged with the world without being worldly, in order to make our culture(s) more Christ-like.

This topic is a central theme of Cruciform, as the subtitle of the site indicates: exploring the intersection of Christianity and culture. In this post I’d like to introduce this topic and note some of its key points.

Bringing transformation to our culture can often be a challenge, for the reason found in the title of this post: “in the world but not of the world”. As Christians -- and in a particular way as lay Christians -- we are called to live in, to act in, to be in the world, but not to be of the world, and getting that distinction right is crucial if we are to most effectively engage the culture in which we live, if we are to make a difference, if we are to make an impact rather than just be impacted on.

There are really two different issues at play here: the first is the task of engaging the culture in which we find ourselves by evaluating it: analyzing it, sifting it, determining its principles and presuppositions, embracing its truth, goodness and beauty while discarding its error, evil and ugliness, etc.; the second is the task of engaging that culture by creating new culture, culture which more deeply reflects reality, culture which more fully embodies truth, goodness and beauty, culture which makes us look both out and within in new ways.

Think of the first task as the movie critic and the second as the movie maker: they are obviously different roles, but they are both important and essential. And in some way, we are all called to do both. How? That’s the question that we’re going to examine and answer in future posts.

What has been your experience of being a “movie critic” or “movie maker”?

Sunday, May 03, 2015

Honey vs. Vinegar

But I'm also a convert to this approach, and a work-in-progress at that... after over 20 years of internet arguing, I've simply been more successful when I've bitten my tongue and at least tried to rein in my desire to unload on the abortion-rights advocate/atheist/fundamentalist Baptist/liberal Catholic with whom I'm talking.

The problem for me is simply that I love to argue, as family and high school classmates can tell you. But the point in evangelization isn't to win arguments but to win souls, and in my experience, the latter is no guarantee of the former.

Let me give an example.

Back in February of 2003 I discovered a forerunner of the New Atheists: The Raving Atheist. I alluded indirectly to him in a couple of posts, and as a result, found myself the recipient of his Godidiot of the Week award. I engaged him in his comment boxes, doing my best to appeal to his sense of reason and avoid biting back overly much.

A couple days later, he wrote this post:

A Valentine’s Day Olive Branch

February 14, 2003 | No Comments

Via Veritas, this sensitive, intelligent and excellent new pro-life blog, After Abortion. It appears, so far, to be firmly grounded in the only true sources of morality — human emotion and experience. Yes, there’ll be a fair amount of God-talk, but I’ll overlook it in the service of a good cause.

See what you get when you’re nice to me?

After this, there was little interaction with Raving... our conversations didn't seem to go anywhere, and he seemed to most enjoy getting those who disagreed with him riled up. I didn't want to let that happen, so our interactions came to an end.

Six years ago, I was mildly surprised (but not shocked) to discover that The Raving Atheist had converted, and was now The Raving Theist. I commented on one of the newer posts, congratulated him and asked if I'd have to give my previous award back. :-)

In an email response, Raving wrote the following:

Dear Chris,

Thanks for your kind and thoughtful comment on my blog.

I thought of you a couple of months ago when I left this comment on the personal blog of my friend Carla, the team leader for Operation Outcry Wisconsin and a moderator at Jill Stanek's blog. As you can see from the last line of that comment, and as I have told countless friends, my debate with you in early 2003 is what led to my pro-life advocacy. Feeling uneasy about the way I had treated you, I went to you blog, found a link to After Abortion and posted it on my blog as an "olive branch" (the link to that post is here; the link to it from Carla's blog broke after my recent changeover to WordPress). That link led to a friendship with Emily Peterson, which led to my involvement with Ashli's McCall's pro-life work after I met her in the comments at AA. I never would have found that blog if you had not directed my attention to it; and I would never have linked to it had you not been so civil. [emphasis added]

You can keep the Godidiot award, but I'll give you something better: credit for so many e-mails like the two below received recently at Beyond Morning Sickness. They're a small sampling of the 1,500 we've received over the past eighteen months.

You've saved quite a few lives.

Yours in Christ,

The Raving Theist

Now, I'm not prepared to agree with Raving's claim that I've saved lives... a few steps too removed for me to feel I can take any credit for that. But I do want to note what I bolded: at least in this instance, turning the other internet cheek had an impact, even if I didn't know it back in February of '03.

By virtue of our baptism, we are all missionaries and evangelists, and it's incumbent upon us that we employ methods which will bear the most fruit, even if it remains hidden from us.

Thursday, April 30, 2015

Praying with Scripture

In fact, one of the most powerful of the many forms of prayer in the Christian tradition is reflection and meditation on the words of the Bible. And even within this form of prayer are a variety of specific ways of doing so.One form of praying with Scripture that’s very ancient but has also seen a resurgence among Christians over the last few decades is called lectio divina (LEK-tseeo dee-VEE-na), which is latin for divine reading. This is the approach that I (attempt to!) use, and I'd like to explain it a bit here.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="397"]